The words are the point

A guest post by Jackie Pick on poet Andrea Gibson's life, death, and work

As a Coloradan, I am dismayed that our poet laureate Andrea Gibson was not on my radar until their death last week. And then they were everywhere—every time I opened Facebook, that was nearly all I saw. Which, to be honest, was a welcome contrast from the stream of horrifying and despicable news. I watched the video of Gibson reading “Love Letter from the Afterlife” and wept. I read tribute after tribute and poem after poem and couldn’t believe I had not read their work until now—how was that possible?

And then I read my friend (and one of my favorite writers) Jackie Pick’s Facebook post and was absolutely blown away by how much she captured. I am in awe of the depth of her perspective on what it feels like to be a writer and why words matter to us so deeply. I’m going to turn it over to Jackie now—she manages to excavate truth like nobody else, with a voice so unique and generous and powerful, just like Andrea Gibson.

If you have a tribute or reflection to share on Andrea Gibson’s life, death, and work, please email it to us at herstoriessummit @ gmail.com. We’d love to publish the words of other midlife women on the impact of the loss of this beautiful voice that many of us may be discovering for the first time.

I hadn’t read their work yet. Not until they died earlier this week and, like clockwork, or maybe like one of those music boxes that only plays when grief turns the key, people I love and admire flooded the world with fragments of their voice. Poems, mostly, and pleas. Things that sounded a bit like prayer.

Everyone said: Read them.

Everyone meant: Let them live a little longer.

That's the thing about words. If we use them well, they linger. Not forever, probably, but long enough for someone to find them when they need them. Long enough to be picked up like a shell and turned over thoughtfully in the hand.

They were surrounded by people who invited their words on speaking, loving, and living. People who listened, then, radically, said, “Go on.” And then — most rare of all — loved them back with something approaching ferocity, the kind of love that doesn’t waver when things get messy.

I understand that. I do. It’s part of why we write.

That’s why a rejection, when you’re trying to reach someone, feels like a small death, or a heavy door slamming shut on you and your future ghost. Which might be the same thing.

Rejection says, “You may not go on. Not like this and not through me.”

Writers deal with that kind of perishing. Sometimes it’s self-inflicted, which is its own agony.

When we try to speak plainly about unfairness, about small absurdities, about injustices and unkindness, someone always seems to pucker and say, “This isn’t the time,” or “Couldn’t you put it more nicely?”

That’s when I sour a bit. Just a bit. I don’t want to pucker, too, when you ask for those words to make you comfortable.

Comfort is not the point.

The words are the point.

Words can reach across astonishing distances, bend time, and build bridges. They can even, on occasion, get someone to admit they were wrong. This is vanishingly rare, of course, but it does happen, if we’re willing to listen. And even then, well, it takes the best words to do the work.

No, that’s not right.

It’s the love inside the words that does the work. Love we’re supposed to have for one another, even when it comes out sideways, all gloppy and weird.

Especially then, I guess, because sometimes love looks like fury. It should, honestly, when we’ve forgotten how to care properly for each other. That’s the issue. Not the words, the life behind them.

I do not want to be with the deeply pickled thinkers and talkers. I don’t mind a little tang. A little sour on the outside, like those candies that attack your tongue and make your eyes water. The brief-suffering candies. They’re surprising, but the surprise wears off, and something sweeter follows if you keep going. (No, not like that. Ew, and no, thank you.)

I hope to be among the ones who invite people’s words, who take care of them in their fragility and aliveness, and who treat them with at least curiosity. Or fury, if that’s warranted, if the sweetness never comes.

Forever is what we say when we don’t know how long love lasts, and we tend to use it when we mean “a bit longer than expected.” Words are a kind of forever.

Which is all just to say, I found I had a copy of Lord of the Butterflies. I’ll let you know how it goes.

That concludes today’s guided ramble.

—Jackie Pick

When I read Jackie’s words last week, my first thought was, “This is why I will love and defend the art of personal essay until my dying breath.” I don’t care if reported essays or “how-to” pieces are more marketable—I will always want to find pieces of myself in other writers’ words. Sometimes that vulnerability and perspective only comes from a personal essay or memoir. And I think it will always be my favorite style of writing.

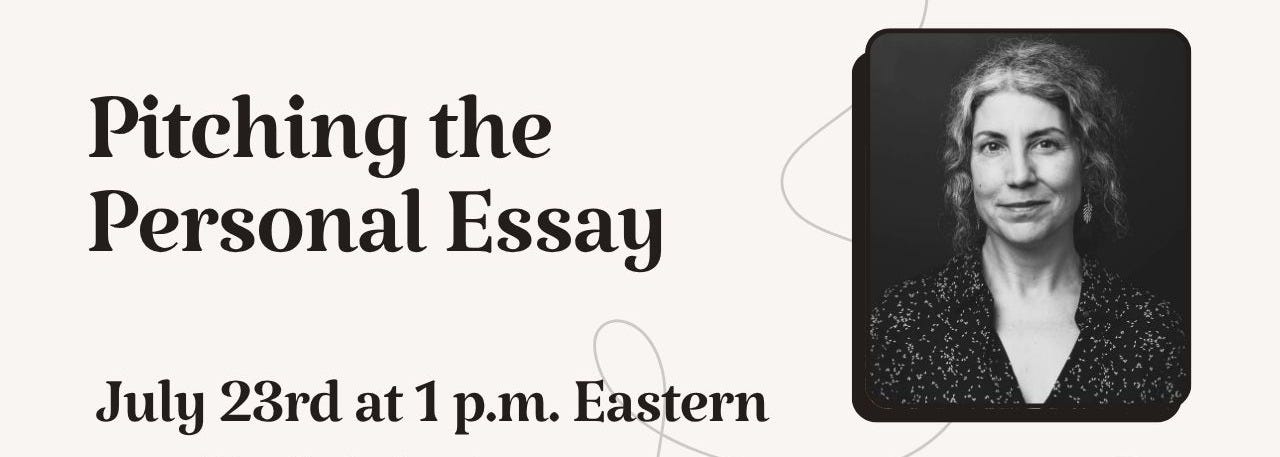

But as an essayist, many of us feel discouraged that there is seemingly no place for our stories in the publishing landscape. I’m inviting you to join us tomorrow as Natalie Serianni guides us through the process of pitching personal essay, which is a bewildering and discouraging prospect for many writers.

This session will be recorded, so please register even if you can’t catch it live. We’ll send the replay and resources the following day. Natalie is a generous guide and thorough, effective teacher and it’s always an honor to learn from her.

Lovely!