Can I Call Myself An Orphan at 49?

Co-editor Jessica Smock writes about what it means to live without your parents at midlife.

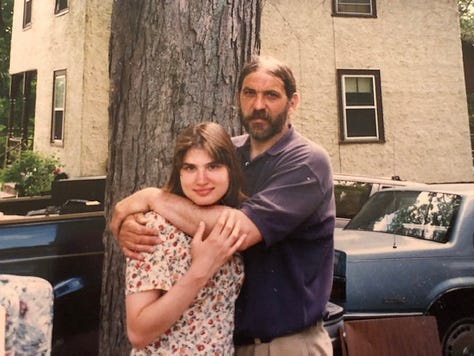

On a snowy night in early December in upstate New York almost four years ago, when my mom died in her bed surrounded by my sister, my brother, and me, I became an orphan. My dad had passed away 16 years earlier at 53 from lung cancer, the same cancer that destroyed my mom.

Orphan is a term we collectively reserve for children, alone in the world, after a devastating tragedy or two claims the lives of their parents.

I was 45 and still felt like something profoundly wrong had occurred in the universe.

Here I was, older by decades from the old-timey orphans I conjured in my head when I heard the term (because I’m a GenXer, I first think of Cassandra and Justin Batemen – sorry, James – in Little House on the Prairie, standing and sobbing after watching their parents’ wagon roll down a hill to their deaths).

I am not a child of tragedy, weeping in my bonnet, abandoned on a prairie. I am a married, middle-aged mom of two kids, with a suburban house, a mortgage, a messy SUV, pets, deadlines, appointments, and an acute case of perimenopause. But I still felt a sense of orphanage, of vulnerability and perilousness and ineffable loss.

As of this weekend, my dad has now been gone 20 years. I’m now only a few years younger than he was when he died. My father didn’t live long enough to see his children marry or meet any of his six grandchildren.

My mom did live long enough, and even though my parents died younger than most, I do realize of course that it’s the natural order of things for children to lose their parents.

If this is the natural way of the world, then why did I feel — and continue to feel — so adrift and untethered?

The truth is that (at least for me) what no one tells you is that there is no expiration date for needing your parents.

You are now alive on this planet without the people who made you who you are, who gave you your name and helped to forge your identity. Your backup is gone — metaphorically, in the sense that you are the next generation who will face death, but also literally, because there is no adult in charge for you to call when you need to be rescued or even just reminded of your simple inner goodness.

I realized this in the first days, weeks and months of grieving for my mom, which for me unfortunately corresponded with the early days of the pandemic.

When my mom was alive, my mom and I would talk over the phone or Facebook messenger frequently, often multiple times daily. In between calls and texts, I’d keep a mental running tally of things I wanted to tell her, items so mundane that I often wouldn’t mention them to anyone else, even my husband. Not because they were secret and important and private but because they were precisely the opposite: so profoundly boring that I felt that no one else would want to dissect them in the way my mom would allow me, as she had for my entire life.

After she died, I realized that all of these unspoken conversations about my life were accumulating in my head, with nowhere for them to go. They began to feel like a dangerous pile of combustible material, ready to explode.

In those first months of grief, as the world shut down from the pandemic, I retreated inward, afraid of exploding. My husband told me I’d call for my mom in my sleep, sobbing in the safety of my dreams.

Even though I was constantly surrounded by my children, now doing school at home, and the all-consuming responsibilities of my ordinary (and now extraordinary pandemic) life, I felt truly alone in an unsettling new way for the first time in my life. My parents had their faults, as all do, but they excelled at making us feel that they were on our side, while allowing us to make mistakes. About the important things, there were no judgments, no equivocation. They had our backs. Now, as a parent, I realize how hard and how unique it is to manage this balancing act well: support without stifling, guidance and grace without disapproval.

And now at midlife, with the world gone mad, I realized that I still needed that unconditional feeling of safety and reassurance that only the people who have known you from the moment of your birth can provide, the only ones who hold memories of you as a baby and developing child, of you and all your past selves.

It’s now years later. The pandemic is over. I’ve grown accustomed to living through these middle years without the metaphorical safety net of my parents’ love and support. But there are days when I still feel like I’m missing my North Star, the guiding light that I can look to and orient myself toward. And I know now this will always be so.

Thank you so much, Jessica, for sharing this. It hasn't been quite two years yet since I lost both my parents just 13 days apart. My mom's passing was after a long illness, but my dad's was a shock. I can relate to so much of what you're saying. I kept a running list of things I wanted to tell my parents, too. (I was lucky to be close with them both.) I told my son (who was 17 at the time) that I never really felt like an adult until my parents died. But the quixotic flipside to that is it hit me so hard that I'm now an orphan. Like you, I felt like I'd lost my backup, my North Star. Please know you're not alone, and thanks again so much for sharing your story!

Beautifully written, Jessica. I was just talking to my own mother about this; she is an only child and her parents were on the older side when she was born (37 and 43). Both died in their 80s, but my mom was still young both times; 39 and 50 when they passed. She's nearly 81 now and there are times, this is true, that she feels that untethered sense. And I pre-feel it! I am vastly fortunate to have, at 57, both my parents (my dad is nearing 87) and even though the world is tilting more toward me-helping-them, I still look to them for that center, holder-of-memories thing. I know I'm on borrowed time. I know I'll never be ready.